The Quadrantids can be one of the strongest displays of the year, yet they are difficult to observe. The main factor is that the display of strong activity only has a duration of about 6 hours. The reason the peak is so short is due to the shower’s thin stream of particles and the fact that the Earth crosses the stream at a perpendicular angle. Unlike most meteor showers which originate from comets, the Quadrantids have been found to originate from an asteroid. Asteroid 2003 EH1 takes 5.52 years to orbit the sun once. It is possible that 2003 EH1 is a “dead comet” or a new kind of object being discussed by astronomers sometimes called a “rock comet.”

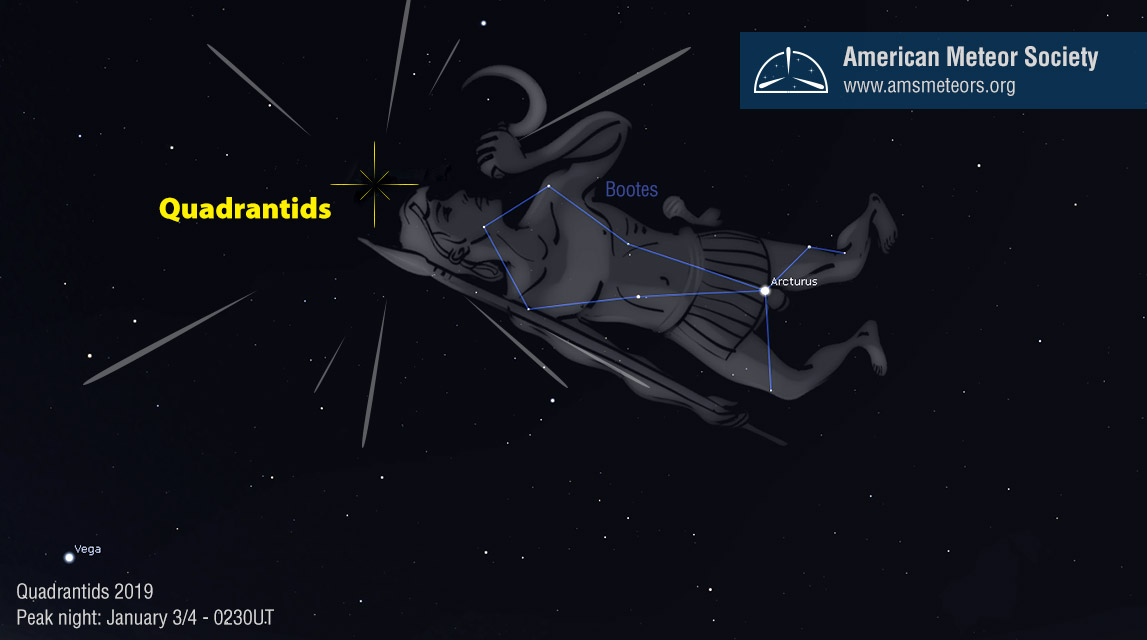

These meteors were first noted in 1825 and appeared to radiate from the obsolete constellation of Quadrans Muralis (Mural Quadrant). Today, this area of the sky lies within the boundaries of the constellation of Boötes the herdsman. During early January nights as seen from the northern hemisphere, this area of the sky lies very low in the northwest in the evening sky. Very little activity is normally seen at this time. As the night progresses this area of the sky swings some 40 degrees beneath the northern celestial pole. From areas south of 40 degrees north latitude, it actually passes below the horizon. It then begins a slow rise into the northeastern sky where it obtains a useful altitude around 02:00 local standard time (depending on your latitude). It is between this time and dawn that you will have your best chance to view these meteors. If the peak occurs during this time you will be in for a treat as rates could exceed 100 per hour as seen from rural locations.

According to the International Meteor Organization’s 2020 Meteor Shower Calendar* the Quadrantids are predicted to peak near 08:20 Universal Time on January 4, 2020. For North American observers this corresponds to 03:20 EST, 02:20 CST, 01:20 MST, and 12:20 PST on the morning of January 4, 2020. This timing is favorable for the western Atlantic region and eastern North America. In western North America the radiant will be low in the northeastern sky and rates will be reduced. All potential observers in North America should start viewing an hour before these times just in case the peak occurs early. Luckily the 60% illuminated waxing moon will set near 01:00 local standard time and will not be a factor except near the west coast of North America.

The best strategy to see the most activity is to face the northeast quadrant of the sky and center your view about half-way up in the sky. By facing this direction you be able to see meteors shoot out of the radiant in all directions. This will make it easy to differentiate between the Quadrantids and random meteors from other sources. To provide a scientific useful observing session one needs to carefully note the starting and ending time of your session and the time each meteor appears. The type of meteor needs to be recorded as well as its magnitude. Other parameters that can be recorded are colors, velocity (degrees per second or verbal description) and whether the meteor left a persistent train. Fireballs should be noted and a separate online form filled out after the session at: https://fireball.amsmeteors.org/members/imo/report_intro/

Serious observers should watch for at least an hour as numerous peaks and valleys of activity will occur. If you only few for a short time it may coincide with a lull of activity. Watching for at least an hour guarantees you will get to see the best this display has to offer. The serious observer is also encouraged to fill out a visual observing form on the website of the International Meteor Organization. You must register to use the form but this is free. The registration site is located at: https://www.imo.net/members/imo_registration/register/

While filling out the visual meteor form be sure to limit your periods to no more than 20 meteors each. This usually ranges from 5 minutes to an hour, depending on the activity.

The average Quadrantid meteor is usually fairly bright and easily seen. But be aware for faint meteors as these are usually numerous, especially at times of high activity. The Quadrantids are not known for their persistent trains, yet I would expect that nearly all of the brightest members would leave a trace. Quadrantid fireballs are rare but they do occur and can be extremely bright.

While the average Quadrantid is fairly bright, this shower is not photogenic unless you take time exposures during maximum activity. The brightest meteors will show up well in prints but most of the captured meteors will only appear as faint streaks. Attaching your camera to a driven mount is highly recommended as this will keep the stars as pinpoints and the meteors as streaks.

This illustration above depicts the Quadrantid radiant as seen during the morning hours looking low toward the northeast. The brilliant star Arcturus is a good guide to this area of the sky. All Quadrantid meteors will trace back to the radiant area located in northern Bootes. From the southern hemisphere the radiant is located much lower in the northern sky therefore rates will be greatly reduced. There are several other minor showers active during this time plus random meteors that will appear in different paths than the Quadrantids with different velocities.

In 2021, the Quadrantids are predicted to peak near 14:51 UT on January 3rd. This timing coincides with sunrise on the Pacific Coast of North America. Alaska and Hawaii are favored locations for this display but most other locations are out of luck. The moon will be a waning gibbous, only 3 days after full so moonlight will be a problem. So if your skies are clear this January 4th, don’t miss this display of celestial fireworks!

*https://www.imo.net/files/meteor-shower/cal2020.pdf page 4

You saw something bright and fast? Like a huge shooting star? Report it: it may be a fireball.

You saw something bright and fast? Like a huge shooting star? Report it: it may be a fireball.  You counted meteors last night? Share your results with us!

You counted meteors last night? Share your results with us!  You took a photo of a meteor or fireball? You have a screenshot of your cam? Share it with us!

You took a photo of a meteor or fireball? You have a screenshot of your cam? Share it with us!  You caught a meteor or fireball on video? Share your video with us!

You caught a meteor or fireball on video? Share your video with us!

2 comments

I hace registerd 46 quadrantids. Two very nice bolids in the night morning 4.1.2020 even iff there have came clouds. VladoBahyl

At Southern Tyrolia I could observe 91 meteors visually in 5 hrs., 76 of them Quadrantids. None was brighter than -3 mag. In the same time my camera recorded 308 meteors, 209 of them Quadrantids. Composite image following soon on the IMO website. Herzliche Grüße, Peter C. Slansky, Munich