Results of the 1998 Leonid Observations

|

|

Leoniden-Feuerkugel über dem Observatorium Ulaan Baatar am

16. November 1998, 19:26 UT, während der Feuerkugel-Aktivität.

Helligkeit etwa -8m. Foto auf Ilford Delta 400 mit

Fish eye Objektiv f/3.5, f=35 mm (6x6),

10 Minuten belichtet.

Leonid fireball over the Ulaan Baatar observatory on November 16, 1998,

19:26 UT.

Apparent magnitude -8m. Photo taken with a fish eye

lens f/3.5, f=35 mm (6x6-film) on Ilford

Delta 400 film, exposed for 10 minutes.

Höher aufgelöstes Bild / higher resolution image (150 kB gif)

|

|

Nachleuchten von zwei Leoniden-Feuerkugeln am 16. November 1998.

Einige dieser Spuren waren bis zu 30 Minuten lang sichtbar,

so daß mehrere Schweife zugleich am Himmel standen.

Foto auf Ilford Delta 400 mit

Fish eye Objektiv f/3.5, f=35 mm (6x6).

Persistent train of two Leonid fireballs on November 16, 1998.

Some of the trains lasted up to 30 minutes. So there were

occasionally several trains visible in the sky. Photo taken with a fish eye

lens f/3.5, f=35 mm (6x6-film) on Ilford

Delta 400 film. |

|

Fotos von Nachleuchterscheinungen lassen sich oft schwer als

solche erkennen. Das Summenbild entstand aus der Überlagerung

der nachfolgend gezeigten Phasen.

Photos of persistent trains often look very strange. This

image is the sum of the phases shown below. |

|

Nachleuchten einer Leoniden-Feuerkugel am 16. November 1998.

als Zeitraffer-Darstellung. Das Nachleuchten war für

rund 30 Minuten sichtbar. Aufnahme mit einer der AKM-Videokameras,

bedient von Wolfgang Hinz.

Persistent train of a Leonid fireball on November 16, 1998.

Some of the trains lasted up to 30 minutes. So there were

occasionally several trains visible in the sky. This sequence

is taken from a video of the AKM, operated by Wolfgang Hinz. |

Updates of the Leonid activity are published at the

IMO web page.

There is a

first report about results from global visual data.

Summary of the 1998 Leonids:

The 1998 return of the Leonids consisted of 2 maxima of the

ZHR: One at lambda=234.52° (eq. J2000) =1998 November 17,

1h 40m UT with ZHR=340±20.

The actual `storm' component

of the Leonid meteroid stream turned out to be weak in 1998

with a peak at lambda=235.308° (1998 November 17,

20h 30m UT) reaching ZHR=180±20.

The first component is chracterized by an extremely low

population index of r=1.19±0.02 at lambda=234.43

(1998 November 16, 23h 30m UT),

whereas relatively high values of r=2.00±0.05 are found

between lambda=235.15° and lambda=235.32°

(1998 November 17, 16h 40m - 20h 50m UT).

The full width at half maximum of the background component

is 17 hours, that of the `storm' component is 0.75 hours.

The highest number density in the stream occurred between

lambda=235.2° and 235.3°, i.e. during the passage

of the storm component.

Aktuelle Informationen über die Leoniden-Aktivität sind

auf der IMO Webseite

zu finden.

Seit dem 9.12. gibt es dort auch

Resultate einer ersten Auswertung globaler visueller Daten

(in englisch).

Kurze Zusammenfassung der 1998er Leoniden:

Die Leoniden zeigten 1998 zwei grundverschiedene Maxima in der

ZHR: Eines bei lambda=234.52° (eq. J2000) = 1998 November 17,

1h 40m UT) mit ZHR=340±20.

Die eigentliche `Sturm'-Komponente der Leoniden blieb relativ schwach

und erreichte ihr Maximum bei lambda=235.308° (1998 November 17,

20h 30m UT) mit einer ZHR=180±20.

Die erste Komponente ist durch einen extrem niedrigen

Populationsindex r=1.19±0.02 bei lambda=234.43

(1998 November 16, 23h 30m UT) gekennzeichnet,

während zwischen lambda=235.15° und lambda=235.32°

(1998 November 17, 16h 40m - 20h 50m UT) vergleichsweise ein

hoher Wert von r=2.00±0.05 gefunden wurde.

Die Halbwertsbreite der (hellen) Hintergrund-Komponente

beträgt 17 Stunden, die der `Sturm'-Komponente nur 0.75 Stunden.

Die höchste Teilchendichte im Strom trat zwischen

lambda=235.2° und 235.3° auf, d.h. während des

Durchgangs durch die `Sturm'-Komponente.

From the Canadians at the UB site / Von unseren kanadischen Mitbeobachtern

Information about the 1998 Leonids

Report from the AKM Leonid expedition "ALEX 98"

complete illustrated report / der komplette bericht mit Bildern.

ALEX 98: A few photos / eininge Bilder

From: Daniel Fischer

How the major international expeditions near Ulaanbaatar fared

By Daniel Fischer, science writer, Koenigswinter, Germany

(currently in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia)

Report posted Nov. 20, 1998, courtesy of the International School of UB

About 30 professional and amateur meteor specialists from Canada, the

United States, Germany and several Eastern European countries have

followed the much anticipated 1998 activities of the Leonid

meteors for four consecutive nights from the Khurel Togoot observatory

10 km SE of the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar and from another site 50

km to the South. The sky conditions were mostly fine for the entire

interval (Nov. 15 to 18 UTC) and particularly excellent during the

night of expected maximum activity (Nov. 17 UTC), with limiting

magnitudes for visual observers better than 6.0 - but temperatures

dropping to -30 degrees centigrade!

The highly unexpected development of the 1998 Leonids, with high

fireball activity way *before* the night of nodal crossing but no storm

or even noticeable enhancement of activity around the crossing time is

widely known by now - see e.g. the still evolving tabulation and ZHR

plot at www.imo.net/news. The Mongolian observations (not included

there at the time of this writing) were carried out by a high-profile

joint Canadian-U.S. team led by Peter Brown (a grad student from

Ontario Western University) and represented by Col. S.P. Worden of the

U.S. Air Force, a 14-head German expedition (including the author) led

by Juergen Rendtel, as well as several Slovakian and Croatian

astronomers.

During the "maximum" night the Khurel Togoot observatory - normally a

largely deserted place no longer maintained as an active astronomical

research facility - was also host to a surprisingly large number of

journalists called there by the Americans and Canadians. Most were

international correspondents based in UB, but one had actually flown in

from Canada. By pure coincidence a handful of bright meteors kept the

spirits of the freezing crowd high just when Leo's head rose

around midnight Mongolian time (16:00 UTC on Nov. 17). But there would

be no replay of the stunning fireball show from 20 hours ago: Mainly

faint meteors could be spotted, and in particular no increase of the

rate when the 'magical' time of nodal crossing (ca. 3:30 local time)

approached.

At 2:20 Mongolian time (18:20 UTC) Col. Worden broke the bad news to

the press: "We're not seeing any increase that would indicate we'll

have a major storm in the next few hours," he stated and suggested that

one might as well go home. "Do you have any idea what happened?"

someone inquired - Worden: "No!" But let there be no mistake: Last

night's "very very strong bright shower of fireballs," according to

Worden, "was probably one of the more impressive fireball shows on

record." And he even referred to the German amateurs on the site:

"Veteran meteor observers among both the German team and our team say

that this is the most impressive fireball display they've ever seen."

And for him personally - a solar astronomer by training - "that's

the most impressive thing I've ever seen in the sky."

Amazingly the fireball storm - if one chooses to call that rare

phenomenon that - had been a global phenomenon: It had "persisted

obviously for at least 18 hours, because we have reports from

across Europe and N. America, some of them visible in daylight - this

is a very unusual situation," Worden summarized the first news that had

reached him. (Even 3 days later the detailed activity profile is

unclear as may teams haven't had an opportunity to report their data

in; it seems however that Europe got at least as high a rate as Eastern

Asia, with ZHR values approaching 500.)

A preponderance of fireballs long before nodal crossing is not exactly

new, however, as Worden reminded the reporters: "1965 had a broad peak

of very very bright meteors that lasted for 36 hours" - and was

followed by a no-show at nodal crossing. 1966, however, had then

brought a tremendous meteor storm at crossing time. For 1998 nearly all

models had anticipated a profile similar to 1966, with a pronounced

although much smaller peak at nodal crossing. Why the forecasts failed

so completely is now a major mystery. It only seems clear that the big

particles that the Earth had encountered well before - but not during

nodal crossing had been released by comet Tempel-Tuttle several hundred

years ago. Since there were so many, Tempel-Tuttle must have

experienced "a pretty major set of events" (Worden) back then. The

small particles the Earth was encountering right now in contrast were

young.

With these fresh insights into the vagaries of meteoritical science

and its strong resemblance to long-term weather forecasting - swallowed

with the help of a few free beers (courtesy of the U.S. embassy) most

of the press had left by 3:30 a.m., leaving behind the astronomers on

the observatory who had largely missed Worden's 'official' cancellation

of the show. There were the Germans from the AKM (Arbeitskreis Meteore)

who had largely gathered on an isolated rock and were recording the

meteor activity with an array of video cameras with image intensifiers,

photographic cameras and visually. Last night individual observers had

seen up to 100 meteors in one hour, most of them very bright or

fireballs, often leaving spectacular trains behind (this number,

corrected for geometrical and other effects, corresponds to a ZHR

of about 250).

Now still some 35 to 40 meteors could be spotted in an hour, but the

fireballs were largely gone, and the ZHR had clearly started to

decline. And by the next night (18/19 Nov.) it would have

dropped off dramatically, to some 10 Leonids per hour. The observing

logs, photographs (hopefully) and especially the roughly 100 hours of

videotape from all 4 nights will be a major source for further studies,

perhaps helping in the end to explain "what went wrong" or rather

why everything went so differently from the expectations this year.

Rather similar data material has been collected by the Canadian-U.S.

expedition: Here, too, a battery of video cameras had been pointed at

the sky, even from two sites (to get redundancy plus 3D vectors for

selected meteors), and visual counts had been made. But the highly

organized effort had had a second objective well beyond basic research:

The visual counts as well as the data gleaned in real-time from one of

the video cameras (by an experimental computer program, 'Meteorscan',

as well as from someone watching a monitor) were telephoned every 15

minutes to Canada. From there the information - now transformed to

ZHR's was eventually passed on to the Air Force's Space (Weather)

Forecast Center in Colorado, which would have warned satellite

operators in case of a real storm brewing.

None had been, of course, and no obvious satellite anomalies were

reported either: The Mongolian experiment had mainly been a

demonstration of principle. But interestingly the prolonged exposure to

comparatively large meteoroids for 24 hours could in principle be as

harmful as a strong but short peak of activity. The further analysis of

the Mongolian tapes and data in the coming months will help to quantify

this possibility - and will hopefully lead to better predictions for

the 1999 Leonids.

And the generally positive experience with the real-time analysis of

meteor videos could one day lead to a world-wide network of automated

monitoring stations - perhaps associated with an already existing

network of U.S.A.F. telescopes keeping an eye on the Sun. The 1998

Leonids didn't live up to some peoples' expectations, no doubt, but

they will eventually bring forward meteor science a great deal. And on

an 'operational' level they have already made history.

Some raw results from the AKM Leonid expedition "ALEX 98"

Vorläufige Daten (visuell) / preliminary visual data

Leoniden Ulaan Baatar, Mongolia

107deg 03' E; 47deg 52' N

November 16-17:

Jürgen Rendtel (RENJU)

period UT min LM LEO

1613 1652 38 6.23 5

1652 1720 27 6.25 12

1720 1738 17 6.28 8

1738 1748 10 6.30 11

1811 1823 12 6.30 8

1823 1831 8 6.29 6

1831 1846 15 6.27 17

1846 1900 13 6.27 9

1908 1925 16 6.27 12

1925 1927 2 6.24 12

1927 1935 8 6.15 8

1935 1941 6 6.15 6

2043 2100 16 6.20 16

2100 2106 6 6.19 15

2106 2118 12 6.17 17

2118 2126 8 6.17 18

2126 2135 9 6.17 19

2135 2140 5 6.17 12

2140 2147 7 6.17 12

2147 2155 8 6.17 10

2155 2204 9 6.15 22

2204 2212 8 6.15 12

2212 2220 8 6.15 15

LEO Helligkeiten / magnitude data

November 16-17

RENJU

-15 -14 -13 -12 -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 TOT

1613-1941

1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 2 6.5 10.5 10 22 25 12 13.5 6 3 0.5 115

2043-2220

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 2 0.5 4.5 14.5 21.5 17.5 19.5 28.5 21 18.5 10.5 5.5 0 167

Sirko Molau (MOLSI)

period UT min LM LEO

1629 1701 32 6.27 3

1701 1724 23 6.37 5

1737 1752 14 6.33 14

1752 1814 22 6.30 18

1814 1832 18 6.33 23

1832 1851 19 6.33 15

1919 1938 19 6.00 23

2104 2116 12 6.00 25

2119 2133 14 6.10 30

2135 2148 13 6.13 31

2148 2205 17 6.13 27

2207 2219 12 6.10 16

LEO Helligkeiten / magnitude data

November 16-17

MOLSI, 1629-2219

-15 -14 -13 -12 -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 TOT

1 0 0 2 0 0 0 1 2 4 3 7 9 14 22 29 28 33 33 37 7 0 232

November 17-18:

Jürgen Rendtel (RENJU)

period UT min LM LEO

1600 1626 25 6.27 4

1626 1640 13 6.27 3

1640 1700 20 6.30 6

1718 1740 21 6.32 12

1740 1800 20 6.30 12

1800 1822 21 6.30 9

1840 1908 27 6.32 25

1908 1926 17 6.32 17

1926 1935 8 6.30 5

1935 1952 16 6.30 16

1952 2003 10 6.30 9

2008 2022 14 6.28 19

2022 2039 16 6.28 19

2040 2049 9 6.28 14

2049 2057 8 6.28 5

2112 2118 6 6.32 5

2118 2137 18 6.32 20

2137 2152 14 6.30 12

2152 2200 8 6.28 6

2200 2207 7 6.25 12

LEO Helligkeiten / magnitude data

November 17-18

RENJU, 1600-2207

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 TOT

1 1.5 3 4.5 12 16.5 35 40.5 50.5 32 27.5 10 234

Sirko Molau (MOLSI)

period UT min LM LEO

1606 1700 54 6.33 12

1728 1800 32 6.36 12

1800 1832 26 6.36 12

1832 1858 26 6.33 16

1858 1916 18 6.36 16

1941 1958 17 6.33 13

2000 2012 12 6.33 16

2012 2022 10 6.33 19

2022 2034 12 6.33 18

2034 2044 10 6.33 17

2049 2105 16 6.33 18

2105 2112 7 6.33 13

2118 2137 19 6.33 28

2137 2152 15 6.33 16

2152 2205 13 6.20 16

LEO Helligkeiten / magnitude data

November 17-18

MOLSI, 1606-2205

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 TOT

0 0 3 3 23 30 33 41 48 39 24 0 244

"ALEX 98"-Images

|

Main building of the Khurel Togoot observatory near Ulaan Baatar.

Hauptgebäude des Khurel Togoot Observatoriums nahe Ulan Bator.

|

|

Sirko Molau with the setup of our video cameras in front of a

small building of the observatory.

Sirko Molau mit den AKM-Videokameras vor einem kleinen

Nebengebäude der Sternwarte.

|

|

Wolfgang Hinz operated the video camera for the trains. He had to move

the camera to the loaction of a bright meteor as fast as possible.

Wolfgang Hinz betreute die Schweif-Kamera. Die wichtigste Aufgabe:

Unmittelbar nach dem Erscheinen einer Feuerkugel mußte die

Kamera in die entsprechende Richtung geschwenkt werden.

|

|

Inside the video operator's room.

Schaltzentrale der Videotechnik.

|

|

We met "Mongolian yak-boys" during our expedition before we went

to the observatory.

Mongolische Reiter in der weiten Steppe auf dem Weg zu ihren Yaks.

|

|

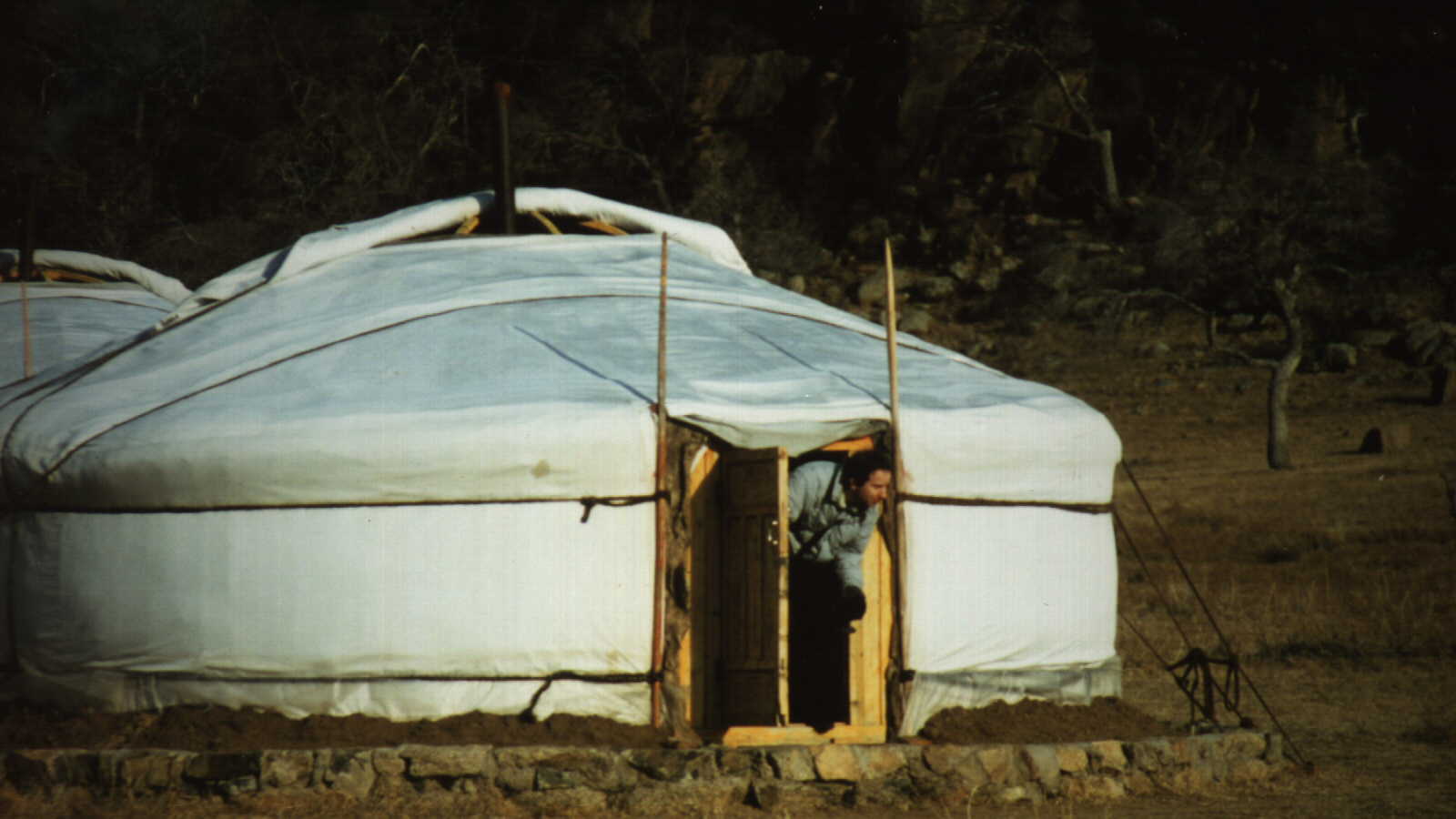

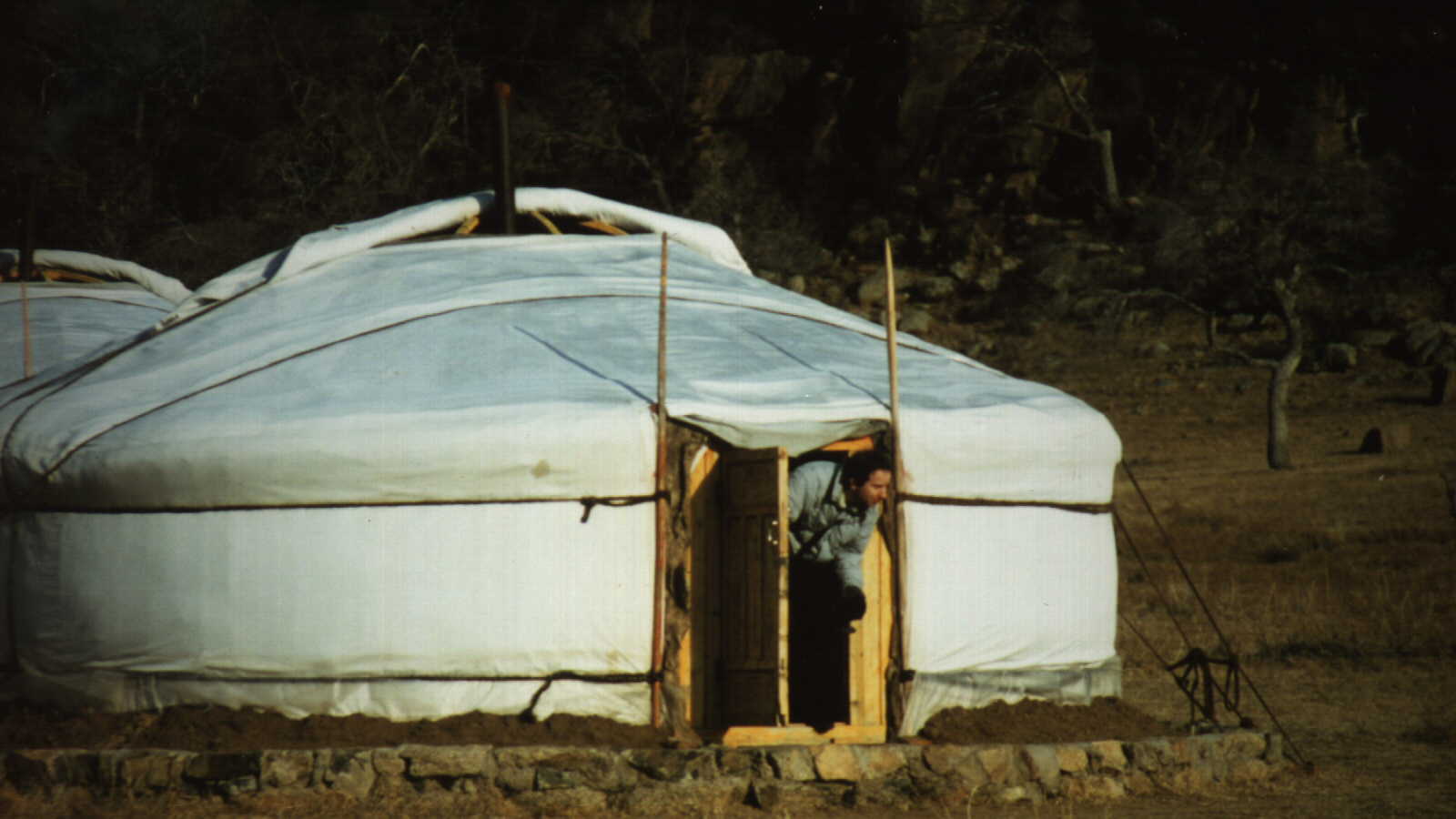

The traditional Mongolian ger (tent) was a comfortable

place during our stay in the steppe - but mind your head!

Die traditionelle mongolische Jurte erwies sich als bequeme

und warme Unterkunft - nur mit dem Kopf mußte man

sehr aufpassen.

|

|

Warm clothing was essential to observe for several hours with

outside temperatures below -30 deg C.

Die sorgfältig ausgewälte Expeditionskleidung war angesichts

von -30 Grad nicht umsonst.

|

|

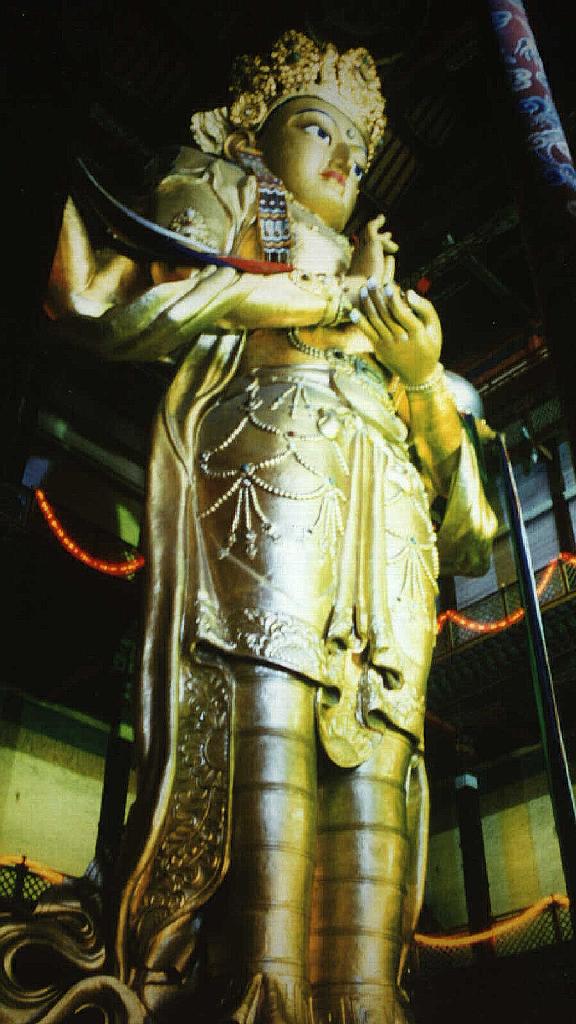

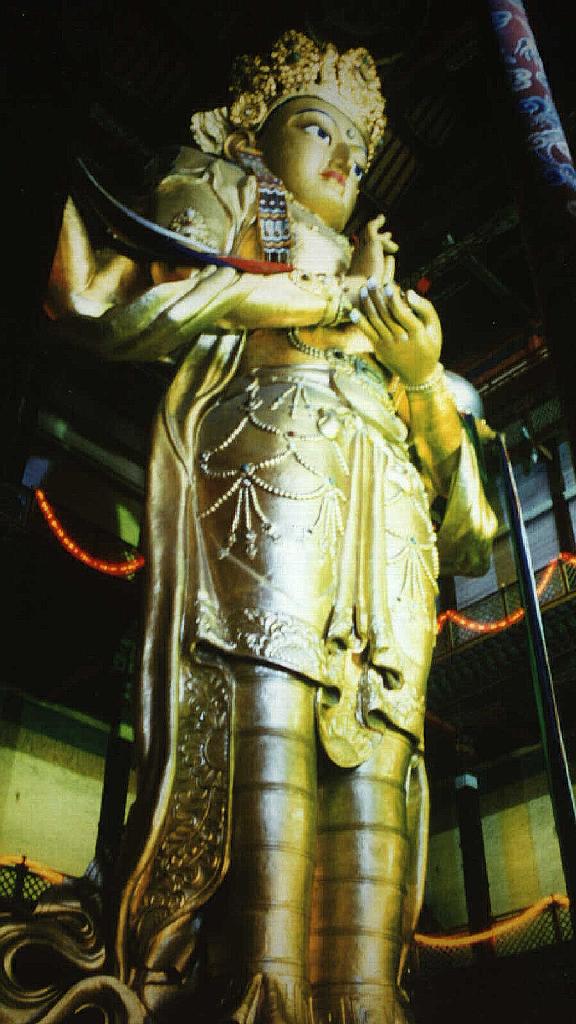

A giant Buddha statue (24 m) is in the Gandan monastery in

Ulaan Baatar.

Wir schauten uns zu Beginn nicht nur diese riesige Buddhastatue

im Gandan Kloster in UB an, sondern drehten auch etliche

Gebetsmülen mit der Bitte um gutes Wetter - mit

Erfolg, wie man sah.

|

last updated: / letzte Änderung:

Designed for Netscape Navigator · Dec 1998 · © JR