This is a topic which is sometimes found in newspaper articles: a “hot, smoking crater”, or a “wildfire” was triggered just after a fireball was seen in a given region of the Earth. Is the link between the two events real, or is it just coincidental? A few pieces of information may help understand why a meteorite fall can’t be the direct source of such terrestrial events.

A farm fire in Italy due to a fireball on July 23rd, 2024?

On July 25th, 2024 , Roberto G., a regular reader and meteor news provider sent us this message, : “In newspaper, there is a piece of news that a fireball triggered a fire in Cesena (Italy): https://corrieredibologna.corriere.it/notizie/cronaca/24_luglio_25/cesena-incendio-devasta-un-azienda-agricola-un-bagliore-nel-cielo-poi-le-fiamme-b5d690ad-f343-4142-bf11-0660d5281xlk.shtml“ (see article translation below).

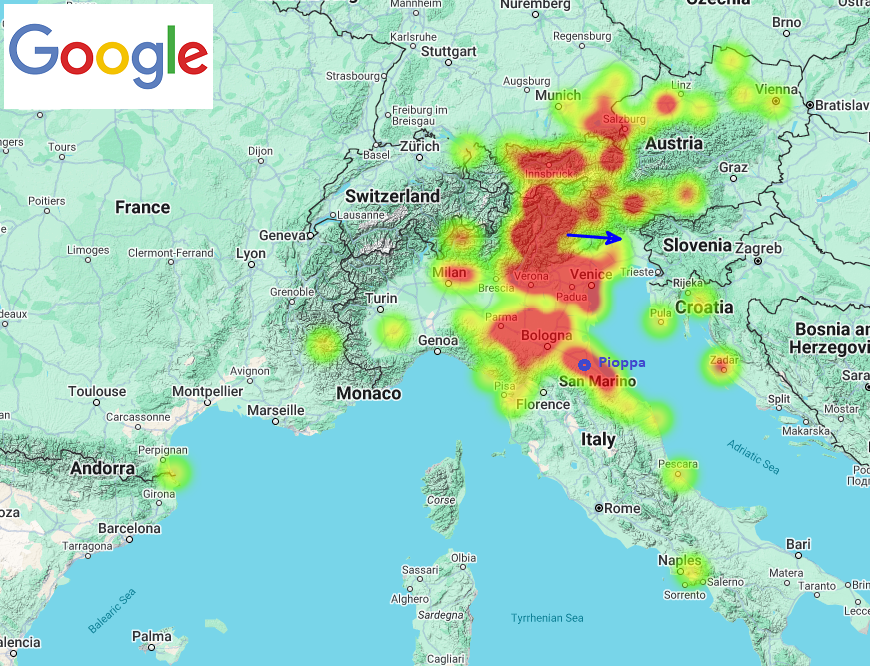

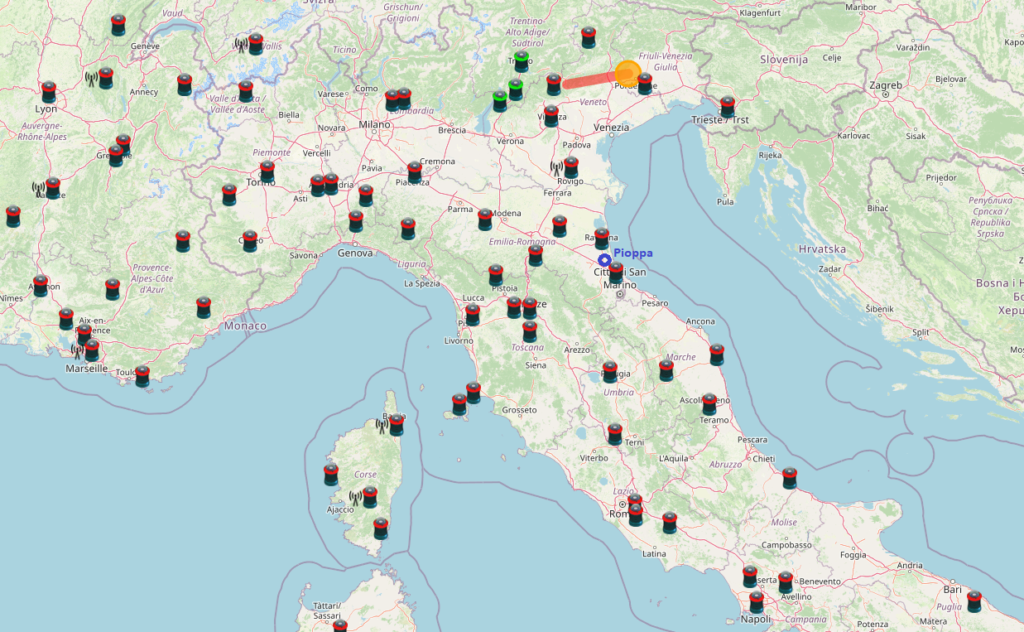

The fireball (event #3622-2024) was widely observed and reported by nearly 200 people on July 23rd, 2024, at 19h 31min UT (21h 31min CEST), from Northern Italy, Austria, France, Germany and Croatia (Figure 2). It was also captured by 3 cameras of PRISMA network (Figures 3 & 4). Those observations and recording allow to calculate the atmopsheric path of the meteoroid that was at the origin of the bright meteor (Figures 2 & 4).

Such pieces of information, and other physical parameters of a meteorite fall and meteor observation give clue of the potential link between a fireball/meteorite fall and a wildfire.

A misleading distance

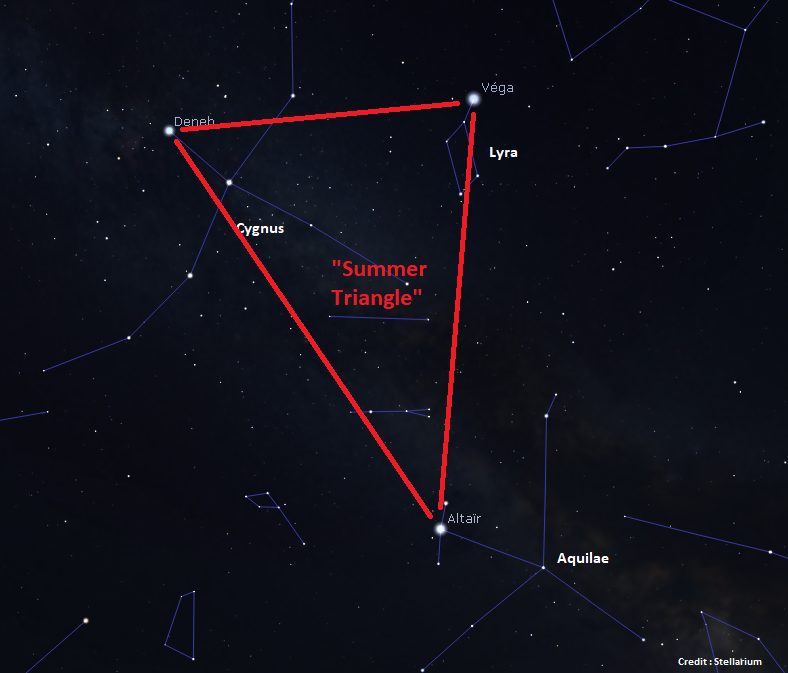

During the nightime, estimating distances can be difficult. No lights, so hard to determine how far is an object, especially when it’s in the sky, where the only parameters the brain can analyze are the apparent speed, and the brightness! This is why bright stars SEEM to appear closer to us than dim ones. In reality, the resulting brightness of a star is the combination of two main parameters : distance… and size! Which makes impossible for a human being to determine if a given star is close or not. For example, if you look at the famous “Summer Triangle” in the sky right now, two bright stars have nearly the same magnitude: Deneb (in Cygnus) and Altair (in Aquila). Altair is a small star (2 solar diameters), but quite close to us (around 16 year-light). Deneb is… 100 times bigger (around 200 times the size of the Sun), but… 100 of times further away (1 600 year-light)! So no one is able to determine distances in the sky, using our senses only.

Meteors usually appear to move fast, and sometimes very fast. Fireballs are bright meteors, so not only do they appear to travel fast, but they are also very bright. Compared to the static, dim background of stars, our brain immediately thinks fireballs are very close objects. So close, that sometimes one imagine it fell in our neighbouring garden, or behind a close hill! In fact, meteors are usually 60 to 120 km high in altitude… and hundreds of kilometers away! In the case of July 23rd, 2024, 19h 31min UT fireball, the farm fire occurred in Pioppa (Cesena, Italy), from where the fireball was observed. But at the time, according to PRISMA calculations of the trajectory (Figure 4), the fireball was traveling… 200 km North!

A mysterious “dark flight”

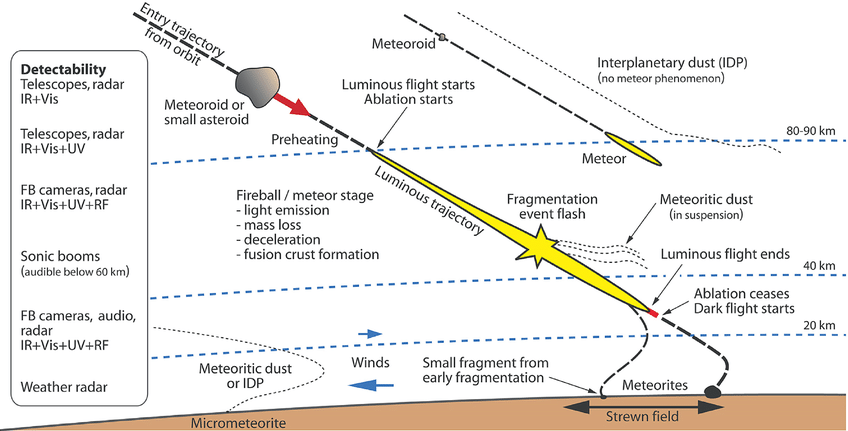

Another point often forgotten is the way a meteoroid behaves when it enters the atmosphere. A meteoroid is a piece of interplanetary rock, ranging from sub-millimeter to meter-size object. When it enters the atmosphere, its speed ranges from 12 km/s to 72 km/s, which is very fast. Even if atmosphere is not very dense at high altitude, it has an influence on the meteoroid, seen its speed: the friction on its surface makes the rock sublimates, and the hit atmosphere molecules win energy they emit back under the form of light. An observer will see a bright phenomenon moving in the sky: a meteor. Most observed meteor are visible between 120 and 80 km altitude. For bigger meteoroids, it takes more time to sublimate, and they can dive deeper in the atmosphere, reaching 30 and sometimes 20 km altitude while still being visible. But even if parts of the rock survive the atmospheric entry, the meteor will fade and disappear, as its speed decreases due to friction of the dense atmosphere, eventually reaching terminal velocity, which is approximately 500km/hour. This invisible portion of the fall of the meteoroid at terminal velocity is called the “dark flight” (Figure 6). This is the hardest part of the trajectory to model, as it’s not visible, and highly dependent on the local meteorological conditions (winds, for instance). But it explains why the end of an observed meteor can be tens of kilometers of the real meteorite strewn field.

Meteorites are cold

As previously explained, meteoroids are interplanetary rocks. And in space, temperatures are freezing. thus a meteoroid is thus very cold for its entire life in space. When it enters the atmosphere, its surface is heated to high temperatures, but the inner portion of the meteor remains very cold. And during its free fall at a much slower velocity, the atmosphere will cool the heated surface. The 9-year-old girl who saw a meteorite falling from a fig tree on August 25, described it as lukewarm on surface, and cold inside. So nor the temperature, neither the speed of the meteoroid when it hits the ground can be the direct source of a fire.

Conclusion

A fireball or a meteorite fall can not be the direct cause of a fire. Of course it could fall on an electrical transformer, cause a shortcut, which triggers a spark which starts a fire. But that’s another story…

Original article translation:

In Cesena, a fire devastates a farm and kills two cows: ‘Perhaps the fragment of a fireball rained down from the sky’

by Enea Conti

It is not ruled out that the fire that destroyed a farm may have been caused by the fragment of a fireball. The fire brigade has reported the incident to the European Space Agency and the Air Force.

‘The fire broke out immediately after a flash in the sky’. In Pioppa, a rural village of Cesena, the origin of a fire that devastated a farm is being investigated, with flames destroying the sheds and killing two cows in a few hours: the case seems to be a detective story, because the origin of the fire has not yet been clarified and it is not excluded that it may have been caused by a fragment of a fireball that streaked the skies over Northern Italy on the evening of 23 July, more or less at the same time – 9.00 p.m. 30 – when the flames broke out on the farm in Pioppa.

The coincidence was brought to light by some locals, who were heard by the State Police. The officers, in turn, had been alerted by the fire brigade, as is the procedure when arson is suspected.

Cesena farm fire: ‘Arson suspected’

The fire brigade in Cesena on the evening of Tuesday, 23 July had to work overtime. The fire was only put out at five o’clock after almost eight hours of work. The fire brigade teams immediately suspected that the origin of the fire was arson. In a night of work, however, no traces of an ignition, or of fuel that the hypothetical arsonists might have used to start the flames, emerged.

‘Radioactivity ruled out’

The scientific team of the fire brigade that arrived from Bologna also found no clear traces of ignition. This is why, after the reports of witnesses who had told of having observed the fireball, instrumental examinations were carried out to understand whether the possible fall of a fragment could have caused the fire.

And the only method that could clarify this on the spot was the analysis of possible radioactive traces, which, however, were not found. On the other hand, it seems quite unlikely that a short circuit caused the accident, although this hypothesis has not been ruled out either.

The fire brigade reported the incident to the ESA

In the meantime, the fire brigade has reported everything to the ESA, the European Space Agency, and to the Air Force, in the hope of dispelling any doubts about the bolide fragment hypothesis.

The event, i.e. the passage of the fireball over Italian skies, actually occurred at 9.30 p.m., at the same time that the flames broke out inside the farm. Coincidence or not, it is worth clarifying what phenomenon this is.

Fireball and meteors: the latest sightings

A fireball is a meteor brighter than Venus, often consisting of fragments of asteroids or comets, or in some cases even space junk (e.g. from artificial satellites). The fireball of 23 July was sighted in Tuscany, Marche, Emilia-Romagna, Lombardy, Piedmont, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Trentino-Alto Adige. Foreign chronicles also report sightings in Austria, Croatia, France and Germany.

It is not easy to spot them, but the passages of these celestial bodies represent well-known events: on 4 June, another meteor was sighted in Italy, in February, the fragment of a bolide was found in Matera on a balcony.

You saw something bright and fast? Like a huge shooting star? Report it: it may be a fireball.

You saw something bright and fast? Like a huge shooting star? Report it: it may be a fireball.  You counted meteors last night? Share your results with us!

You counted meteors last night? Share your results with us!  You took a photo of a meteor or fireball? You have a screenshot of your cam? Share it with us!

You took a photo of a meteor or fireball? You have a screenshot of your cam? Share it with us!  You caught a meteor or fireball on video? Share your video with us!

You caught a meteor or fireball on video? Share your video with us!